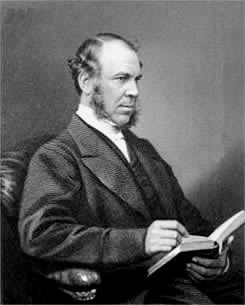

Rev. J. C. Ryle D.D. 1816–1900AD

NO UNCERTAIN SOUND.

His first charge to the New Diocese of Liverpool, October 19, 1881. [1]

My Reverend and Lay Brethren, We are gathered together today on an occasion of much interest and real solemnity. This is the primary visitation of the first Bishop of a new English Diocese. How many visitations may be held, and how many Episcopal Charges delivered before the end of all things, no man can tell. Let us pray that there may be always found in this Diocese a trumpet which shall give no ‘uncertain sound,’ and a Bishop who shall promote the real interests of the Reformed Church of England.

I ask you to believe that I meet you with a deep sense of my own weakness and fallibility. I have been called unexpectedly to be the chief pastor of a Diocese of vast importance and very exceptional character, a Diocese in which, to use the words of Scripture, ‘there remaineth yet very much land to be possessed.’ (Joshua 13. 1.) I feel keenly how much is expected of a bishop in these days, and how little in reality he can do how much the difficulties of his office are increased by our unhappy divisions—and how hard it is for any bishop to do his duty without causing disappointment to some, and giving offence to others. All these things, I repeat, I feel very keenly. But I see no reason for despondency or despair. With prayer, and pains, and faith in Jesus Christ, nothing is impossible. No doubt there is much to be done by the Church in Lancashire. But He who was the Lord God of Joshua and the Israelites, when they crossed Jordan and entered Canaan, is not dead, but alive. If we have His blessing, and if we have a good understanding between Bishop, clergy, and laity, I have a firm conviction that great results will follow from the formation of the new See of Liverpool, and that in a few years the Church of England will occupy a very different, and an improved position in the West Derby Hundred of this County.

In a new Diocese like ours, accurate statistics are of the utmost importance. We cannot possibly form an estimate of ‘things that are wanting’ unless we thoroughly understand our position. I make no apology, therefore, in the outset of my Charge, for calling your attention to certain broad facts which we shall do well to remember. There are some very peculiar features in the Diocese of Liverpool, which distinguish it from any other Diocese in the land, and I shall try to set them before you in order.

(1) In a geographical point of view, our Diocese covers a smaller area of ground than any other in Great Britain, with the single exception of London. There are 181,000 acres in the Diocese of London, and 262,000 in Liverpool. It consists simply of the West Derby Hundred of the County of Lancaster, a district so thoroughly intersected with railways that a Bishop residing in Liverpool may reach almost every church in his Diocese in about an hour.

(2) The population of our Diocese is little less than 1,100,000 according to the last census. Nine English dioceses show a larger return: viz., London, Winchester, Lichfield, Rochester, Worcester, York, Durham, and Manchester. In none, however, with the exception of London, is the population per acre so dense and closely packed together. Liverpool and its suburbs alone make up at least 650,000 dwellers in streets out of the 1,100,000. Wigan and its suburbs, Warrington, St. Helen’s, Southport, Farnworth, Widnes, and Garston supply an aggregate of at least 250,000 more. It is probable that not more than 200,000 of the inhabitants of our Diocese can be found outside towns. In hardly any part of the Queen’s dominions has the population increased so rapidly, chiefly from the demand for labour, and consequent immigration in order to meet that demand, during the last decennial period.

(3) The nationalities, employments, and occupations of our large population are curiously diversified. Perhaps there is hardly a district in Great Britain in which you will see such an extraordinary variety of classes. In Liverpool itself you have an enormous body of inhabitants connected with our docks and shipping, and an incessant stream of emigrants from the Continent of Europe to America. You have smoky manufactories and squalid poverty at one end of the city, and within two or three miles you have fine streets and comparative wealth. In Wigan, Warrington, St. Helen’s, Widnes, and the districts round these places, you have swarms of people employed in collieries, iron foundries, cotton manufactories, glass and chemical works. Around Ormskirk, Sefton, Hale, and Speke, you will see admirable farming. In no part of England, perhaps, will you find such a variety of callings, and all followed with a restless activity. And, though last, not least, in no part will you find such a mixture of the Queen’s subjects. Out of the 1,100,000 inhabitants of our Diocese, there is reason to believe that at least 200,000 are Irish, and 50,000 Welsh. Of the numbers of the Scotch I have heard no estimate. But I am greatly mistaken if the Scotch element is not very largely represented in such a busy and prosperous community as the great commercial outport of Lancashire and Yorkshire.

(4) The spiritual provision which the Church of England has hitherto made for the 1,100,000 inhabitants of our Diocese appears painfully inadequate. In touching this subject, I would have it distinctly understood that I do not ignore the good work which has been done by our Nonconformist brethren. I thankfully acknowledge the service they have rendered to Christ’s cause in Liverpool. Nor can I forget the praiseworthy zeal with which the Romish Church has provided for its adherents. Still, after every deduction, I think it is impossible to deny that there are myriads of dwellers in our Diocese for whose souls no means of grace are provided, and whose condition urgently demands the attention of Churchmen. If the Established Church of this country claims to be ‘the Church of the people,’ it is her bounden duty to see that no part of ‘the people’ are left like sheep without a shepherd. If she claims to be a territorial, and not a congregational Church, she should never rest till there is neither a street, nor a lane, nor a house, nor a garret, nor a cellar, nor a family, which is not regularly looked after, and provided with the offer of means of grace by her officials. Of course she cannot make people value religion, or care for the means she provides. But her aim should be to produce such a state of things, that no one shall be able to say, ‘I am no man’s parishioner. I am never visited or spoken to: no one cares for my soul.’

How far we are at present from this desirable state of things most of you know as well as myself. The full and complete returns to my Visitation Articles of inquiry (for which, let me say, I am truly grateful) reveal the painful fact that there are many parishes in our Diocese in which the population has far outgrown the power of any single incumbent to superintend it, and in which there would be abundant work for three or four independent parochial incumbents, if they could be provided. At the present moment we have only 200 incumbents and 140 curates for 1,100,000 people. I venture boldly to say that there is not another diocese in all England in which the disproportion between the demands on the Church and the supply the Church has provided, is so startling and so serious. In the Diocese of Norwich[2] you will find 914 benefices and 1160 clergy for 660,000 people. Here in the Diocese of Liverpool you have 200 benefices, 340 clergy, and 1,100,000 souls. How glaring is the contrast!

But even the statement I have just made conveys a very inadequate idea of the financial position of the Church in the Diocese of Liverpool. In an old diocese like Norwich a large proportion of the benefices are rectories or vicarages, and endowed with tithes or land. In our new Diocese I suppose that there were not altogether twenty-five churches so endowed 200 years ago, and there are not more now. The greater part of our existing churches are comparatively modern, and destitute of anything worth calling an endowment. Their incumbents are entirely dependent on a precarious and varying income, arising from fees, pew-rents, or offertories, and are often most miserably ill-paid. In fact, if such a thing as disestablishment with disendowment were ever to come, I suspect there is no diocese in England where the clergy would suffer less from it than ours! The great majority have neither tithes nor land of which they could be deprived.

The reasons of this extraordinary state of things are not hard to discover. The population of the West Derby Hundred has grown with unprecedented rapidity during the last 180 years. Hamlets have swelled into villages, and villages into towns. Our great seaport on the Mersey has leaped with a few bounds into the foremost position in the Queen’s dominions, and, with Lancashire and Yorkshire behind her, seems likely to grow still more. The great development of mining and manufacturing industry in the east side of our Diocese has brought together an immense number of labourers. Both inside and outside of Liverpool there has been a constant influx and immigration of people into the district. But all this time, unhappily, the Church of England, until of late years, has done comparatively little for the souls who were brought together. In days gone by, I am afraid, fortunes were too often made and carried away, while the hands who helped to make them were forgotten and neglected.

The consequences of this want of means of grace are precisely what might be expected by every student of the Bible and human nature. Let alone and left to themselves, great masses of our population appear practically to have no religion at all. No one can read the police reports, or the account of coroners’ inquests in our Liverpool daily papers, without coming across harrowing records of drunkenness, immorality and crime. No intelligent observer can walk about the more densely peopled quarters of this city, for instance, upon a Sunday, and avoid the painful conclusion that many men and women whom he sees never attend any place of worship. Their dresses, their looks, their whole demeanour supply evidence which cannot be mistaken. For idleness, or gossiping, or visiting, or drinking when public houses are open and drink can be bought, they are ready enough, but not for God’s house. It is a sight which is most distressing to every friend of Christianity and morality. From keeping no Sabbath to having no God there is but a flight of steps. But who can wonder? As things are at present, there must be thousands of our people who are completely let alone. If every adult man and woman in Liverpool, who was in good health and able to leave home safely, resolved next Sunday to attend a place of worship, it is quite certain that every church and chapel and mission room in our city would be filled to suffocation, and that myriads would be obliged to return home from want of accommodation!

Such is a brief sketch of the condition of things which confronts the first Bishop of Liverpool. Such are the facts which I ask the Churchmen of this new Diocese to consider, face, and grapple with. I am not aware that I have exaggerated or overstated anything. On the contrary, when I look at the statistics of certain parishes, which I will not name, I believe I have understated my case. Nor shall I waste your time with useless lamentation and fault-finding. I prefer taking it for granted that we all agree that something ought to be done, and the only question is what that something ought to be. Lancashire men, I know, are practical and business-like men. I wish to approach the subject in a business-like way.

At the very outset of our inquiry, I desire to acknowledge with deep thankfulness the large amount of good work which I have found going on in the Diocese of Liverpool under the hands of Churchmen. If any one, dwelling in a distant part of England and unacquainted with Lancashire, supposes that the Bishop of the newly-created See on the banks of the Mersey found nothing like Church-work going on, no organization, no machinery, no philanthropic Institutions, no religious Societies, I beg to tell him that he is entirely mistaken. The idea that the Church of England in the West Derby Hundred would be found a kind of ecclesiastical wilderness, like a newly-founded Colonial Diocese, is a delusion. Nothing can be further from the truth. Thanks to the diligent care of the Bishops of Chester, who formerly had the oversight of this part of Lancashire, and thanks to the voluntary zeal of resident clergy and laity, I find a large amount of diocesan machinery in excellent working order—machinery which will bear a favourable comparison with that of the oldest diocese in the land. I find ruri-decanal conferences in every deanery. I find the causes of education, of temperance, of Sunday schools, of Foreign and Home Missions systematically and well supported. I find a powerful Scripture Readers’ Society, and a Bible Women’s Association in Liverpool itself. I find an admirable Sailors’ Home. I find nine Hospitals. I find special work going on, by the general co-operation of all professing Christians, for special classes, such as seamen, shipwrights, waggoners, and cab and omnibus drivers. The orphan, the blind, the deaf and dumb, the street Arabs, and gutter children, even the newsboys, are not forgotten. I find a most useful Diocesan Finance Association. Above all, I find a body of clergy, however small and overworked, and many of them sadly ill-paid, who are, as a body, admirable representatives of the Church of England. All these are facts which I most thankfully acknowledge and would never ignore for a moment. Yet I am sure all whom I address today will agree with me that much remains to be done. And how to set about it, and what to begin with, is the next point to which I propose to direct your attention.

(1) For one thing, then, the Church of England in our Diocese appears to me to want a large multiplication of living agents . When I speak of living agents I mean ordained ministers of the Word. In saying this I wish not to be misunderstood. No one can value more than I do the work of Scripture readers and lay agents. The good that they do in their own province is simply incalculable. But if the Church is to be systematically organised in a new district, and placed on a lasting foundation; if a regular congregation is to be called into existence, the sacraments duly administered, and our liturgical services set up; the unit in our calculation must be a presbyter. The dwellers within every new district should be able to feel that they have their own special minister, and that they are his special parishioners. The lay agent may do excellent service by sowing the seed and cutting down the corn. But if the crop is not to rot on the ground, the sheaves must be bound up and stored away in the barn. And this is the presbyter’s work. The Scripture reader may gather together recruits, and persuade them to enlist in the King’s service. But the presbyter must drill, and train, and discipline them, and show them how to act together, move together, and form an efficient regiment.

My own opinion is most decided, that the Church of England is never in the right position, and can never do her duty as the ‘Church of the people’, and do herself justice, until she has no parochial districts, as a general rule, with a population of more than 5000; and until, for every such parochial district, she has a presbyter in charge. Even 5000 is a large number if a clergyman is a thorough pastor and a house-going man. But allowance must, of course, be made for a certain proportion of Roman Catholics, and Nonconformists, who are looked after by their own ministers. Once let a clergyman’s district exceed 5000, and I am pretty certain it is almost impossible for him to overtake all his work satisfactorily. As for parishes or districts in which there are 10,000, 12,000, 15,000, or 20,000 souls, with only one incumbent, it is useless to suppose that the clergyman of such districts can possibly know or reach a large proportion of his parishioners.

How frightfully undermanned the Church of England is at present in Liverpool must be evident to any one on the slightest reflection! Taking it for granted that there are in this great city and its suburbs 650,000 people, there ought to be 130 parochial districts of 5000 each, and 130 incumbents in charge of these districts. I need hardly remind those whom I address this day, that our present staff of clergymen is lamentably below the figure I have just named. In such a condition of things the Church of England cannot possibly do herself justice, and to expect her to be ‘the Church of the people’ in Liverpool is simply absurd. You might as well send out of the Mersey a Cunard or White Star steamer, with a crew of only twenty men, all told—officers, seamen, engineers, and stokers—and expect her to cross the Atlantic and reach New York in safety. Our first, foremost, and principal want, I unhesitatingly assert, is a large increase of working clergy.

(2) The second chief want of the Church of England in the Diocese of Liverpool appears to me to be a greater number of places of worship . As to the need of more churches in the city of Liverpool itself, a valuable Report was drawn up more than two years ago by a committee appointed by the Bishop of Chester. This Report declared that even then twelve new churches were urgently required, and the proper sites were carefully indicated. Little, however, has been done since the date of that Report, and the necessity is as great now as ever. The population of our huge city seems to grow at the rate of 5000 a year, and to keep pace with this growth one new church ought to be built every year! At present we have not done anything worth mentioning to make up our lost ground. Let it not be forgotten also that in every large parish a plain roomy mission-room for non-liturgical services, prayer-meetings, and the like, is an indispensable part of the parochial machinery, without which no hard-working clergyman can ever work comfortably. How many more of these invaluable rooms we want in Liverpool I will not pretend to say; but in point of usefulness, in order to begin and keep up the Church’s work, I believe they are even more important than churches.

Whether, in the face of the peculiar wants of our city, we ought not to attempt a special Twelve Churches Fund for Liverpool, is a question which is now very much on my mind, and on which I earnestly desire the advice of all the tried and experienced leaders of good work in Liverpool, both clerical and lay. The money ought not to be an insuperable difficulty, I am certain, if there is only the will. The city which, within five years, has twice raised little less than £100,000—once to found its own Bishopric, and once to found a University—is not unequal to raising another £100,000, in order to make the Church of England in Liverpool commensurate with the wants of the people. The money, I repeat, could easily be provided.

Two things only, I hope, would be kept steadily in view, if such a Twelve Churches Fund as I have suggested were ever set on foot. One is, that in every district where a new church is proposed, there should be an active canvass made of the population, and an earnest appeal made to all holders of property to meet the public fund by a local contribution. People never value a new church so much as when they have helped, as far as they can, to build it themselves. The other thing I would name is the importance of studying economy and practical usefulness, as far as possible, in the construction of all new churches built with public money. Let us make the money go as far as possible, and not waste it in needless external decoration, but aim at making the inside as comfortable as possible. When land is very expensive, it is wise to put the school under the church, as at St. Stephen’s, Byrom Street. When the district is low in character, and destitute of good houses, a parsonage should accompany the Church. In every case I strongly recommend a large, commodious vestry , for the use of confirmation classes and communicants’ meetings.

After all, I desire never to forget that other large and important places in the Diocese need new churches as well as Liverpool. The spiritual wants of several other towns are great and crying. No true friend of the Church of England, I am sure, can ever feel satisfied until more places of worship and more clergy are provided for the population of the whole West Derby Hundred. But I reserve any remarks I have to make on this subject for the visitation I propose to hold tomorrow at Wigan.

The great question yet remains to be answered, How are the formidable wants of our new Diocese to be met? To that question I can only give one reply. We have nothing to depend upon except the voluntary liberality of the laity. For the support of the clergyman of a new district of a certain population, for new curates in mining parishes, and in very exceptional cases for assistant curates in very poor, large incumbencies, we may certainly reckon on obtaining, sooner or later, the help of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. But for building new churches, and mission-rooms, and for any large increase of clergy, we must depend, I repeat, on the voluntary help of the laity. I do most earnestly hope that this help will be given. If those admirable institutions, the Diocesan Church Aid Society, and the Diocesan Church Building Society, could each command an income of £10,000 a year, the good that might soon be done is incalculable.

How easily the funds needed might be raised if ALL the Churchmen of the Diocese were alive to their responsibility, and made it a duty to give, may very soon be shown. Few persons have the least idea how small is the number of subscribers to religious objects, and how continually you meet the names of the same noble-minded, large-hearted men in every subscription list you read.[3] There are human mines of wealth in the Hundred of West Derby which have never yet been touched. All the churches we need might soon be built, all the additional clergy might soon be provided, if all lay Churchmen would open their eyes, come forward boldly, and realize the luxury of doing good, and, giving money, to advance the kingdom of God. At present that luxury is only enjoyed by a select few. It ought not to be so.

The plain truth is, that in the matter of giving money to Christ’s cause, the great majority of English Churchmen are sadly behind the times, and want educating. The Scotch Presbyterians, the English Wesleyans, and the Independents ought to put us to shame. We want more men to come forward as the late noble-minded George Moore did in London, and as some have done formerly in Liverpool, saying, ‘I will build a church myself, and will ask no one to help me.’ What huge sums are often wasted on luxuries and recreations, and lost for ever! But who ever found the promises fail about ‘repayment to him that lendeth to the Lord’? Who ever found, on balancing his accounts at the year’s end, that he missed money which he had given to spiritual objects? Who ever came to the Bankruptcy Court by doing good to souls?

After all, though it is only a low motive, rich men should never forget that it is the truest policy and highest wisdom to promote the spread of true religion. Reason itself points out that, in the long run of years, the moral standard of a city or a nation is the grand secret of its prosperity. Gold mines, manufactures, scientific discoveries, docks, roads, eloquent speeches, commercial activity, and democratic institutions are not enough to make or to keep nations great. Tyre and Sidon, Carthage, Athens, Rome, Venice, and Spain and Portugal had plenty of such possessions as these, and yet fell into decay. The sinews of a nation’s strength are truthfulness, honesty, sobriety, purity, temperance, economy, diligence, brotherly kindness, charity among its inhabitants, and, consequently, good credit among mankind. Let those deny this who dare. And will any man say that there is any surer way of producing these characteristics in a people than by encouraging, fostering, spreading, and teaching pure Scriptural Christianity? The man who says there is a surer way must be an infidel. Then, if these things are so, the first duty of the wealthy men in every city ought to be to encourage and countenance religion among the people around them in every possible way. Does a man want his poorer neighbours, and those whom he employs, to be steady, provident, truthful, diligent, temperate, honest, moral, and charitable? Does he, or does he not? If he does, he ought to support religion. To punish vice and yet not cherish virtue, to spend public money on paying police, building jails, and yet not to encourage the increase of ministers and the building of churches, is, to say the least, an absurdly inconsistent policy. The more true religion, the better people! The more good people, the more prosperity! The wealthy men of a city who ignore religion, and coolly declare that they do not care whether the inhabitants are Christians or not, are guilty of an act of suicidal folly. Irreligion, even in a temporal point of view, is the worst enemy of a nation or a city.

Of course I am aware that one favourite answer to my plea for more churches is the unhappy fact that there are existing churches which at present are not filled. ‘Fill your old churches,’ is the cry, ‘and then we will build you new ones.’ Allow me to say that this is an excuse and not an argument. I am not referring to Liverpool especially, when I say that so long as patrons appoint unfit clergymen who have no gifts suited to their position, and so long as the Church makes no provision for pensioning off invalided or superannuated clergymen, so long there will always be found some empty churches. But empty churches at one end of a city are no reason why we should not build new churches at another. All ministers are not equally adapted to all sorts of parishes and population. Only exercise common sense in the choice of a clergyman, and let him be a man who wisely and lovingly preaches, lives and works the Gospel, and I am certain he will never preach to empty benches. There are many proofs in this Diocese that I am saying the truth. But, alas, when people have little will to help Christ’s cause, they never lack reasons to confirm their will! Too many seem to forget that, in the matter of church building, or in any work for Christ, duties are ours, and results are in the hand of God.

(3) The third chief want of the Diocese of Liverpool is one which I feel great difficulty in handling. I refer, of course, to the need for a cathedral suited to the size and wealth of our Diocese, and to the importance of the second city in Great Britain. I approach the subject with delicacy. It is a far wider and deeper one than most people suppose. I am constantly asked, ‘When are you going to begin your cathedral?’ But few seem to realize what the idea involves.

The theory of all cathedrals, no doubt, is an excellent one. Let the principal town of every diocese have a magnificent church, which in architecture and arrangements shall surpass all other churches as much as a Bishop surpasses a presbyter in his official position! Let the services of this church be a model to the whole diocese, and let the public prayer and praise and preaching be a standing pattern of the highest style of Christian worship! Let the management of this church be confided to some grave, learned, and eminent clergyman called a Dean, assisted by three or four other clergymen called Canons! Let these Canons be picked men, selected solely on account of their singular merits, and not for family or political reasons, and famous for deep theological learning, or great preaching power, or wisdom in counsel, or spirituality of life! Let such a choice body as this Dean and Canons be in intimate and friendly connection with the Bishop, be his right hand and his right eye, his counsellors, his helps, his sword, his arrows, and his bow! Let the cathedral body, so constituted, be the heart, and mainspring, and centre of every good work in the diocese! Let its members be well paid, well housed, and have no excuse for not residing in the Cathedral Close the greater part of each year! Let the influence of the cathedral body, as a fountain of spirituality and holiness, be specially felt in the cathedral city! Let its active usefulness be seen in the energetic management of every sort of diocesan machinery for spreading the Gospel at home and abroad! Let Deans and Canons be known and read of all men as ‘burning and shining lights,’ the very cream and flower of Churchmen, and let the cathedral city in consequence become the ecclesiastical Athens of every diocese, the stronghold of Church influence in the district, and the nursery of theological learning! Such, I suppose, is the theory of an English cathedral establishment. Such were the intentions of those who permitted the continued existence of our cathedral bodies at the period of the Reformation. The theory of such a cathedral is excellent. If we had such a cathedral and such a chapter in Liverpool, no one would be more thankful than myself. If any one would offer to build and endow such a cathedral I would heartily welcome the offer.

But let us consider well what we are talking about. Let us count the cost. We must remember at the outset that in this matter the new Diocese of Liverpool starts at an immense disadvantage compared to every new diocese of modern times. Ripon, Manchester, and St. Albans had each a cathedral, or a church fit to be a cathedral, and Ripon and Manchester had each an endowed Chapter. Southwell has a beautiful Minster. Wakefield and Newcastle parish churches are noble buildings, fit to be cathedrals. The Bishop of Truro, no doubt, is building a cathedral. But then the county of Cornwall, which forms his diocese, hardly needs another church to be built in it, and he can easily concentrate all his efforts on his cathedral. Moreover, his cathedral is already endowed with a rich Exeter Canonry. At Liverpool, on the contrary, we have everything to do from the very beginning. We have not a church in our city which is fit to be converted into a cathedral. We have no site for a new cathedral, except one behind the Gymnasium, in a disused cemetery, which many, perhaps, would dislike; and any other site would cost an enormous sum. The cathedral itself, to be worthy of Liverpool, would cost a quarter of a million before it was finished. The Dean, Canons, and cathedral staff would need to be endowed. Even now the maintenance of our present voluntary cathedral services, on a humble scale, is a very grave difficulty. All these are serious considerations. Are we prepared to face a sum of half a million of money? We might face it, of course; but are we prepared?

Let no one misunderstand me. Let no one fancy I object to a cathedral altogether. Nothing of the kind! If any one comes forward with a princely offer like that of the ladies who have built Edinburgh Cathedral, or if any one will do in Liverpool what has been lately done at St. Patrick’s and Christ Church Cathedrals in Dublin, or at St. Finbar’s in Cork, I shall be deeply grateful. For anything I know it may be in the heart of some one even now to do this. I only know that my first and foremost business, as Bishop of a new Diocese, is to provide for preaching the Gospel to souls now entirely neglected, whom no cathedral would touch. My first work at present is to endeavour to provide more clergymen, and more places of worship, and that, so far as I can see, is likely to fill up the few years of my episcopate.

I leave the want of a cathedral here. I believe the matter will be handled fully at the coming Diocesan Conference. Those who handle it will perhaps throw more light on it than I have done. I lay no claim to infallibility, and may be mistaken. I only ask all who handle it to ‘count the cost.’

Before I leave the subject of the wants of the Diocese, I think it would be ungracious and ungrateful if I did not express publicly my thankfulness for many things which I have found here. I have spoken strongly of ‘the things that are wanting. Let me also speak strongly of things that are existing.

(i) I am deeply thankful to find so many clergymen doing solid, good work in the Diocese of Liverpool. I never look for perfection. I suppose that every bishop soon finds that there are ministers and ministers in his diocese-ministers who do little, and ministers who do much. But I doubt extremely whether there are many dioceses in England and Wales where there is so great a proportion of clergymen who are ‘workmen that need not be ashamed,’ and who are quietly and unostentatiously bearing ‘fruit that will remain.’

(ii) I am very thankful for the large number of well-furnished and well-provided churches that I have seen, and the general heartiness and liveliness of the services. I may be allowed to speak of this. I have already preached in more than 90 different churches—nearly half the churches in my Diocese—and my opinion is the result of personal observation. The only thing I have not quite liked has been the extravagantly lavish expenditure, in some cases, on the decoration for Harvest Festivals, when there is so much money needed for many Diocesan objects. These cases are exceptional, I admit; but I must frankly say that I should like to see some limit put to the quantity of decoration. God’s house is not meant to be an Exhibition of flowers, corn, fruit, evergreens, and ferns, but a place for prayer, praise, and preaching of the Word. However, I am willing to suppose that there is such a thing as an excess of well-meant zeal.

(iii) I am thankful for the large number of communicants of the lower classes whom I have seen at some evening communions. I cannot feel the objections that many feel to evening communions. To refuse them in some poor districts would be to repel many wives and mothers from the Lord’s table altogether. For my own personal comfort I certainly prefer receiving the sacrament in the morning. But remembering that the ordinance was originally instituted in the evening, and that our church distinctly calls it the Lord’s Supper , I fail to see how an evening communion can be positively wrong. That the Church of England can gain and keep the affection of the working classes, when she is properly worked, I have always maintained. I see it proved by the evening communions at which I have assisted in Liverpool.

(iv) I am thankful for the interest I find taken in Church Sunday Schools. Since the establishment of Board Schools[4] for the week-days, it is impossible to overrate the importance of Sunday Schools. Without them we should soon have a generation of young people in the land ignorant alike of the Creeds, the Catechism, and the Prayer-book of the Church of England, and utterly unprepared to understand the rite of confirmation. Let me express my earnest hope that the interest in Church Sunday Schools may everywhere deepen and increase, and that those most useful and self-denying persons, the Sunday School teachers, may be encouraged in every way. I believe an efficient body of Sunday School teachers is the right hand of a clergyman.

(v) I am thankful to observe the active and intelligent interest which the laity of the Diocese seem to take in the proceedings of the Church. I have seldom seen a body of churchwardens who appear to come forward and fill their office so efficiently as they appear to do in the churches where I have preached. And I cannot sufficiently commend the invaluable services which many laymen voluntarily render to our Diocesan institutions. All this is as it should be. The laity are ‘the Church’ quite as much as the clergy. When the laity are passive, sleeping partners, and leave the concerns of the Church in the hands of the clergy, it is a symptom of a most unhealthy state of things in the ecclesiastical body. I trust it may never be so in Liverpool.

For all these things which I have named, for the uniform kindness and courtesy which I have received from all, for the general willingness to meet my wishes which I have observed, I desire publicly, at this my Primary Visitation, to express my deep and hearty gratitude. I came among you with much anxiety, expecting far more difficulties and collisions than I have hitherto met with. But you have smoothed my course in many ways, and made my path comparatively easy. I thank God, and I thank you.

I must now turn away from subjects of purely local interest, in order to say something about the general position of the Church of England. I do so with considerable reluctance. The great ecclesiastical questions of the day are of such a burning character that a man cannot handle them without coming into collision with somebody’s cherished opinions. But a Diocese has a right to expect its Bishop to say what he thinks at his Visitation, and I must not disappoint its just expectations. After all, I suppose there is not a clergyman here who would like his Bishop to be a mere colourless nonentity, without any distinct opinions, or to fill the place of a ship’s figure-head, which, however ornamental, adds nothing to the speed or stability of the vessel. I shall, therefore, endeavour to speak out my mind.

Of course we are all apt to exaggerate the importance of our own times. But I venture to think that the present position of the Church of England is more critical and perilous than it has been at any period during the last two centuries. On every side the horizon is dark and lowring. There seem to be breakers ahead and breakers astern, dangers on the right hand and dangers on the left, dangers from without and dangers from within. Whether the good old ship will weather the storm remains to be seen. But I am quite certain that much depends, under God, on the conduct of the crew. If reason and sanctified common sense prevail, we shall live: if not, we shall die.

Concerning dangers from without I shall say little. They arise chiefly from the operations of the Liberation Society. That restless and zealous body, departing widely from the principles of the old Nonconformists, such as Richard Baxter and John Owen, has set itself to promote the disestablishment and disendowment of the Church of England, and to make an end of the union of Church and State. Up to this time, I see no proof that the movement is successful. On the contrary, I have a firm impression that the Church is even stronger now than it was when the agitation first began.

The plain truth is, that the public mind is not prepared for the state of things which disestablishment would bring about, if conducted to its logical consequences. Of course, if the union of Church and State were dissolved, all Churches and sects would be left on a dead level of equality. No favour or privilege would be granted by the State to one more than another. The Infidel, the Deist, the Mahometan, the Socinian, the Jew, the Romanist, the Episcopalian, the Presbyterian, the Congregationalist, the Methodist, the Baptist, all would be regarded with equal indifference. The State itself would have nothing to do with religion, and would leave the supply of it to the principles of free trade and the action of the voluntary system. In a word, the Government of England would allow all its subjects to serve God or Baal, to go to heaven or to another place, just as they pleased. The State would take no cognizance of spiritual matters, and would look on with Epicurean indifference and unconcern. The State would continue to care for the bodies of its subjects, but it would entirely ignore their souls.

Gallio, who thought Christianity was a matter of ‘words and names,’ and ‘cared for none of these things,’ would become the model of an English Statesman. The Sovereign of Great Britain might be a Papist, the Prime Minister a Mahometan, the Lord Chancellor a Jew. Parliament would begin without prayer. Oaths would be dispensed with in Courts of Justice. The next King would be crowned without a religious service in Westminster Abbey. Prisons and workhouses, men-of-war and regiments, would all be left without chaplains. In short, for fear of offending infidels and people who object to the recognition of God by intercessory prayer, I suppose that regimental bands would be logically forbidden to play ‘God Save the Queen.’

Now, does the British public wish to see this state of things brought about? I do not believe it for a moment at present. The public knows that, as matters stand now, the Dissenters have liberty to do anything they like, so long as they can find money to do it. They are under no civil or religious disabilities. They may go where they please, build where they please, preach where they please, and worship as they please, without asking any one’s leave. They can do even more than Churchmen can, and have more liberty. A Churchman cannot go into a clergyman’s parish, however grossly neglected it may be, and build a new church, without obtaining the incumbent’s consent; but any Dissenter can go into that same parish and build a chapel. The public knows that, with all her faults, the Established Church, on the whole, does more good than harm, and that in rural parishes especially disestablishment and disendowment would almost be the death of religion. All these things the public sees and knows; and knowing them, the bulk of Englishmen appear to feel little desire for disestablishment.

For all these reasons I shall not dwell much on the Church’s danger from without. Of course it is impossible to say to what extent we may strengthen the hands of our outward enemies by our own suicidal folly. But so long as the Church is true to herself, and to the great principles of the Reformation, so long, I believe, the laity will not allow her to be disestablished. She will be tested by her fruits. The best ally of the Church Defence Society is the clergyman who preaches the truth, lives the truth, works his district, visits his people, and has a kind word, and a helping hand, and a loving heart ready for every man and woman in his parish. The best friend of the Liberation Society is the indolent clergyman, who is content to preach defective sermons to empty benches, who has few communicants, no parochial machinery, no Sunday Schools, no regular visitation of the sick, no knowledge of most of his people, and just leaves everybody alone. The parish of such a man is the surest and best help to the cause of Liberationism.

The principal dangers of the Church of England arise from within. They consist in the strifes, and conflicts, and controversies which rage so furiously within her pale, and threaten almost to tear her to pieces. We know who has said, ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ It was not so much the army of Titus that destroyed Jerusalem as the internal dissensions of the Jews within the city. I confess I do not fear disestablishment and disendowment half so much as division and disunion among ourselves, and consequent disintegration and disruption.

The chief internal danger of the Church, in my opinion, arises from the continual existence among us of a body of Churchmen who, if words and actions mean anything, seem determined to unprotestantize the Church of England, to reintroduce principles and practices which our forefathers deliberately rejected three centuries ago, and, in one word, to get behind the Protestant Reformation. That there is such a body of Churchmen, that hundreds of them from time to time have shown the tendency of their views by secession to Rome, that for twenty-five years their proceedings have called forth remonstrances and warnings from most of our bishops, that the eyes of all Christendom are fixed on this body and men are watching and wondering whereunto it will grow, that Romanists rejoice in its rise and progress, and all true-hearted Protestants in other lands grieve and mourn—all these, I say, are great patent facts which it is waste of time to prove, because they cannot be denied.

The zeal, earnestness, and self-denial of this body of Churchmen I do not for a moment dispute. But I cannot at all admit that they have any monopoly of these qualifications. Nor can I admit that any quantity of zeal and earnestness confers a licence to introduce ‘divers and strange doctrines’ and practices into our parish churches, and to overstep the limits laid down in the authorized formularies of the Church of England.

But the point to which I want to direct your special attention is this. It is an unhappy fact that the main subject of contention between the school to which I have referred and their opponents, has been for several years the blessed sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. Scores of clergymen have adopted the practice of administering the Lord’s Supper with usages which have been almost entirely laid aside for 300 years, usages to all appearance borrowed from the Church of Rome, usages which even Archbishop Laud in the plenitude of his power never dared to enforce, usages which, to the vast majority of thinking men, seem intended to bring back into our Church that most dangerous of all Romish doctrines, the sacrifice of the Mass.

You are all aware that the legality of these new usages in the administration of the Lord’s Supper has been made the subject of repeated trials, before the highest Law Courts of the realm. The final result has been that almost all have been pronounced distinctly illegal, and that every clergyman who persists in wearing a chasuble, or burning incense, or having lighted candles on the communion table, or mixing water with the sacramental wine, or elevating and adoring the consecrated elements, is doing that which contravenes the doctrine of the Church of England, is putting a sense on the ‘Ornaments Rubric’ which the highest Courts of the realm distinctly condemn, and therefore is breaking the law.

But now comes a miserable fact which constitutes the present greatest danger of the Church of England. Some of those clergymen who have adopted these novel usages in the Lord’s Supper refuse to pay the slightest attention to the judgments of the Law Courts, or to the admonitions of their bishops. In the face of the contemporanea exposito[5] of three centuries, which certainly confirms the interpretation of the Ornaments Rubric given by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council; in the face of the utter absence of anything in our Communion office to confirm their novel views; in the face of their own solemn vow and promise to obey their bishop; they persist in their own way of administering the Lord’s Supper; and for the sake of things which they themselves must allow are not essential to it, they seem prepared to rend in pieces the Church of England.

And worst of all, in all this, they are aided, backed, countenanced, and supported by hundreds of clergymen who never dream of breaking the law themselves, but seem to regard these law-breaking brethren as martyrs, and as excellent, worthy, and persecuted men, who ought to be let alone! If all this does not constitute a most dangerous state of things, I know not what is danger to a Church. Without some change it will be the ruin of the Church of England.

I hear so many foolish and unreasonable things said about the perilous position of matters, which I have tried to describe, that I think it may be useful to offer a few remarks to all men of practical common sense, which may serve to clear the air, and be useful to some.

(1) I sometimes hear it said, that the ecclesiastical lawsuits of recent times about the Lord’s Supper ought never to have been instituted, that law-breaking clergymen might easily have been kept in order by their bishops, and that those who instituted legal proceedings were ‘persecutors’ and troublers of Israel. How the law could be ascertained without a carefully prepared argument before competent judges I fail to see. What likelihood there was of modern law-breakers paying any attention to episcopal admonitions I leave all calm observers to consider. But as to the hard names and bitter epithets heaped on prosecutors, I regard them with sorrow as unworthy of the lips from which they come. Englishmen who remember that the true doctrine of the Lord’s Supper was the very point for which the Marian martyrs went to the stake ought surely not to be surprised if many people are extremely sensitive about the least attempt to bring back the Romish Mass. I for one do not wonder. Thousands of people, I believe, would put up with many ceremonial novelties who would resist to the uttermost any innovations in the Lord’s Supper. The words of Bishop Thirlwall,[6] in his last Charge, are worth remembering: ‘The persons who instituted these proceedings, though to their adversaries they might appear persecutors, could not but look on themselves as simply acting on the defensive, in resistance to an unprovoked and unlawful aggression, and for the purpose of resisting what to them seemed a tremendous evil.’ ( Remains ii. 306.) It is easy and cheap work to call names, and revile opponents as ‘persecutors.’ But the plain truth is, that those who break the law and refuse to obey their bishop are the real persecutors of the Church.

(2) I have heard it said frequently that the interpretation of the Ornaments Rubric, laid down after lawful and deliberate inquiry by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, is altogether incorrect, and, therefore, ought not to be obeyed. I have even heard it said, that their last decision was one ‘of policy, and not of justice.’ I hear such sayings with considerable indifference, and call to mind the old adage, that ‘Defeated litigants always blame the Court in which they fail.’ But broad assertions are not arguments. It is easy for some angry divines to say superciliously that leading English lawyers, of proved intellectual vigour and long experience, are incompetent to handle ecclesiastical subjects, to analyze the language of documents, and weigh the meaning of words in formularies, and that they know nothing about rubrics and Church history, and cannot grasp such matters. But who, I should like to know, will believe all this? The immense majority of thinking men in the House of Lords or the House of Commons, in the Temple or Lincoln’s Inn, in the City or the West End, in Oxford or Cambridge, in Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, or Bristol, will never believe it for a moment, and will think poorly of the sense of those who say such things. As for the unworthy insinuation that eminent English judges of spotless character would ever stain their judicial ermine by deciding ecclesiastical questions in a party spirit, from notions of ‘policy rather than justice,’ and from impure motives, I will not condescend to notice it. I pity alike the men who can make such insinuations, and the men who can believe them.

(3) Sometimes I hear it said that spiritual questions ought to be left to spiritual men, and that a Court composed mainly of laymen, like the judicial Committee, is incompetent to try theological cases. This at first sight appears a very plausible idea; but I do not think it will bear the test of calm consideration. No doubt the present Court of Final Appeal, like every judicial Court composed of men, may have its faults and imperfections, and the Royal Commission now sitting may perhaps suggest improvements. But if the judicial Committee of the Privy Council is to be set aside in ecclesiastical cases, and a so-called spiritual court set up in its stead, I doubt extremely whether a better court, and one which will satisfy the laity, can possibly be constructed. It is easy to find fault with an institution and pull it down, but it is not always so easy to build a better. Where are the constituent parts to come from? Who are to be the new and improved judges? I declare I look over the land from north to south, and from east to west, and I fail to discover the materials out of which your ‘readjusted’ Court of Appeal is to be composed. There may be hidden Daniels ready to come to the judgment-seat of whom I know nothing. But I should be glad to know who they are.

Will you ask the State to sweep away the present Court of Appeal, and compose one of bishops only? I am afraid such a court would never give satisfaction. If there is any one point on which the Guardian and the Record , the Church Times and the Rock are entirely agreed, it is the fallibility of Bishops! Each of these papers would tell you that several English prelates are anything but wise and orthodox, and are not trustworthy judges of disputed questions. But if this is the case, what likelihood is there that the whole Church would be satisfied with their judicial decisions?

Will you turn away from the Bishops, and compose your new Court of Appeal of deans, University professors, and select eminent theologians, picked out of Convocation? Again the same objection applies. He that can run his eye over the list of English deans, or the professional staff at Oxford and Cambridge, and then talk of forming out of that list an unexceptionable tribunal, acceptable to all parties, must be a man of faith bordering on credulity. As to the ‘select eminent theologians,’ I have yet to know who is to have the selection. The very divines whom one school of Churchmen would choose are men whom another school would not allow to be sound ‘theologians’ at all.

The fact is, that the favourite theory of those who would refer all ecclesiastical causes to clerical judges, is a theory which will never work. It sounds plausible at first, and looks well at a distance, but it is utterly unpractical. Laymen, and legal laymen, trained and accustomed to look at all sides of a question, are the only material out of which a satisfactory Court of Appeal can be formed. Ecclesiastics, as a rule, are unfit to be judges. We do not shine on the bench, whatever we may do in the pulpit. If there is one thing that bishops and presbyters rarely possess, it is the judicial mind, and the power of giving an impartial, unbiased decision.[7]

(4) I have heard it said sometimes, that the matters for which the recent objectors to decisions about the Ornaments Rubric contend are mere matters of taste. The whole question, forsooth, is one of aestheticism and ornamentation! Why wrangle and quarrel, some say, about such trifles? I wish I could believe this view. Unhappily there is strong testimony the other way. With the party of whom I am now speaking, the whole value of ceremonial consists in its significance as a visible symbol of doctrine. The evidence of leading men before the Ritual Commission, the language continually used in certain books and manuals about the Lord’s Supper, all tend to show that the question in dispute is, whether in the sacrament there is a propitiatory sacrifice as well as a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, and whether there is a real presence beside that in the hearts of believers. These are not trifles, but serious doctrinal errors, and points on which I am persuaded the bulk of English Churchmen will never tolerate the least approach to the Church of Rome. To use the words of the late Bishop Thirlwall, ‘The real question is, whether our communion office is to be transformed into the closest possible resemblance to the Romish Mass.’ ( Remains ii. 233.) [8]

(5) Last, but not least, I hear it sometimes said, that obedience to rubrics ought to be enforced all round, and that it is not fair to require one clergyman to obey the Ornaments Rubric as interpreted by the Privy Council, while another clergyman is allowed to neglect another rubric altogether. This is a favourite argument in many quarters; but I am unable to see any force in it. In matters like these there is no parallelism whatsoever between acts of omission and acts of addition. To place on the same level the conduct of the man who, in administering the Lord’s Supper, introduces novelties of most serious doctrinal significance, and the conduct of the man who does not observe some petty obsolete direction, of no doctrinal significance at all, is to my mind contrary to common sense. But, after all, complete and perfect obedience to all the rubrics is simply impossible, and I do not suppose there is a single clergyman in England who observes all. The three first rubrics in the Communion Service are illustrations of what I mean. Moreover, the change of laws and customs, and the large liberty now allowed to a clergyman, have rendered some ancient rubrical requirements obsolete and inexpedient. A certain discretion must be allowed to a bishop in the nineteenth century in deciding what the circumstances of the Church require to be observed. If I ask one clergyman to obey the ruling of the Privy Council about the Ornaments Rubric, and to discontinue the use of the chasuble, the incense, the lighted candles, and the like, I do so because of the immense importance of maintaining Protestant views of the Lord’s Supper, and the deep jealousy which prevails among the laity about the appearance of anything like the sacrifice of the Mass. If I decline to ask another clergyman to have matins, and vespers, and saints’ day services, in some huge, over-grown, poor parish in a mining district, or at the North or South end of Liverpool, I decline because I think his time, in the short twelve hours of the day, might be far better employed. He can do far more good by doing things which were flatly forbidden 220 years ago (when our rubrics were last settled), by non-liturgical services in unconsecrated rooms, by Cottage Lectures, by Bible Classes, by Young Men’s Meetings, by Mothers’ Meetings, by Temperance Meetings, by Prayer Meetings, and other well-known modern means of usefulness. And when men tell me that my balances are unjust, and that it is not fair to interfere with the one clergyman and to leave the other clergyman alone, I hear the accusation with indifference. I believe I am doing that which is best for the Church of England, and most likely to advance her interests.

I leave this weary subject here. For dwelling on it at such length, and trying to discuss it from every point of view, I make no apology. The position of the Church is so critical, and the danger so great, that a Bishop has no right to hold his peace. Without some change of weather, or change in men’s minds, or change in the management of the ship, I see nothing before us but shipwreck of the Church of England. I am often disposed to say with Daniel, ‘What shall be the end of these things?’ Let us quietly consider. What are the alternatives?

(1) Shall we give way to the Romanizing party? Shall we try to compel every clergyman in the Church of England to use the chasuble and its accompaniments in the Lord’s Supper, and to turn the sacrament into a sacrifice? God forbid! The idea is ridiculous and impossible. You would raise a storm from the Isle of Wight to Berwick-on-Tweed far worse than the storm of the Commonwealth days. When the sun rises in the west and sets in the east, when the Mersey flows back from Liverpool to the Cheshire Hills, then, and not till then, I believe, will the majority of English Churchmen consent to insult the memory of our Marian martyrs, and return to the Romish Mass. They will never consent.

(2) Shall we adopt the notable plan of throwing open the whole question of usages in the Lord’s Supper, and allowing every clergyman to administer it with any ceremonies he likes? This, I suppose, is the policy of ‘forbearance and toleration’ for which many have petitioned, though how such a policy could be carried out, in the face of the last decisions, I fail to see, except by a special act of Parliament. A more unwise and suicidal policy than this I cannot conceive. You would divide every Diocese into two distinct and sharply-cut parties. You would divide the clergy into two separate classes—those who wore chasubles, and those who did not; and of course there would be no more communion between the two classes. As to the unfortunate Bishops, they must either have no consciences, and see no differences, and be honorary members of all schools of thought, or else they must offend one party of their clergy and please the other. This is indeed a miserable prospect! ‘Forbearance and toleration’ are fine, high-sounding words; but if they mean that every clergyman is to be allowed to do what he likes, they seem to me the certain forerunner of confusion, division, and disruption.[9]

(3) Shall we stand firmly by the last decision of the Law Courts, and refuse to depart from the old paths and old usages about the Lord’s Supper with which our forefathers have been content for 300 years? Hard and painful as the conclusion may appear, I see no alternative. My sentence is that we ought so to stand firm, and to abide the consequences, whatever they may be, whether secession, disestablishment, or disruption. ‘Fiat veritas, ruat coelum.’[10] Remember, in saying this, I am no prophet. I do not know that there would be many secessions, or any at all. It is not those who talk most loudly about seceding who secede at last. But supposing that secession and disruption of the Church of England are the results of the policy which I have just indicated, let us just remember how the matter will appear in the future annals of history. The record will be as follows: ‘In the latter part of the nineteenth century the Established Church of England was destroyed and rent in pieces because of a contention of two parties within her pale, neither of which would give way. One of the two parties persisted in administering the Lord’s Supper with ceremonies borrowed from the Church of Rome, ceremonies not once mentioned in Scripture or the communion office of the Prayer-book, ceremonies decidedly not of the essence of the sacrament, ceremonies condemned by the Courts of law, ceremonies which had not been used for 300 years. The other party steadily refused to depart from the principles on which the Church was reformed in the sixteenth century, and from the customs which had prevailed since the days of Queen Elizabeth. And as neither party would give way, the public got weary, Parliament stepped in, and the Church was disestablished, disendowed, and rent in pieces.’ Now what will the verdict of posterity be? I leave it to yourselves to supply the answer.

I have no wish, in saying this, to be a black prophet. I have great faith in our Church’s tenacity of life. She survived the expulsion of 2000 most able clergymen in 1662 by the Act of Uniformity. She survived the secession of the non jurors, when William III came to the throne. She survived the loss of the Methodist body in the last century. She has survived the departure to their own place of Manning, Newman, Oakley, Faber, the two Wilberforces, and many others in our own day. If she is faithful to Protestant principles, I believe she would survive the secession of the whole ‘English Church Union,’ if they left us next year! But I cannot bring myself to believe yet that the great majority of the members of that body would actually leave the Church of their forefathers, on account of things which they themselves must allow are not essential to the Lord’s Supper. I shall not believe it till I see it.

As to myself, my mind is made up. I mean to abide by the decisions of the Courts of Law, so long as those decisions are not superseded and nullified by Parliament, or reversed. I see no other safe or satisfactory course to adopt. A Bishop who sets himself above the law , and ignores its decrees, is launched on a sea of uncertainties, which I, for one, decline to face. I cannot forget, that as a chief officer of the Church, I am specially bound to set an example of obedience to the powers that be, and to acknowledge the Queen’s authority in things ecclesiastical as well as temporal.

I came to the position I occupy as Bishop of Liverpool with a settled resolution to be just and fair and kind to clergymen of every school of thought, whether High or Low or Broad, or no party. To that resolution I mean to adhere through evil report and good report. Whenever I see in a clergyman hearty working, consistent living, and loyal Churchmanship, I shall be thankful, and ready to help him, though things may be said in his pulpit and done in his parish with which I do not entirely agree. But my clergy must not expect me to sanction and countenance transgressions of the law, and I do entreat them, for the sake of peace, to keep within the limits of the judicial decisions on the great points which have been disputed, argued, and determined in the last few years.

I have long maintained, and still maintain, that every well-constituted National Church ought to be as comprehensive as possible. It should allow large liberty of thought within certain limits. Its ‘necessaria’ should be few and well-defined. Its ‘nonnecessaria’ should be very many. It should make generous allowance for the infinite variety of men’s minds, the curious sensitiveness of scrupulous consciences, and the enormous difficulty of clothing thoughts in language which will not admit of more than one meaning. A sect can afford to be narrow and exclusive: a National Church ought to be liberal, generous, and as ‘large-hearted’ as Solomon. (1 Kings 4. 29.) Above all, the rulers of such a Church should never forget that it is a body of which the members, from the highest minister down to the humblest layman, are all fallen and corrupt creatures, and that their mental errors, as well as their moral delinquencies, demand very tender dealing. The great Master of all Churches was One who would not break a bruised reed or quench smoking flax (Matt. 12. 20), and tolerated much ignorance and many mistakes in His disciples. A National Church must never be ashamed to walk in His steps. To secure the greatest happiness and wealth of the greatest number in the State is the aim of every wise politician. To comprehend and take in, by a well-devised system of scriptural Christianity, the greatest number of Christians in the nation, ought to be the aim of every National Church. To these principles, as an English bishop, I mean to adhere.

Comprehensiveness, such as I have described, I believe to be a peculiar characteristic of the National Church of England. We have within our pale three widely different ‘schools of thought,’ the old historical schools, commonly called High and Low and Broad. They are schools which have existed for nearly three centuries, and, unless human nature greatly alters, I believe they will exist as long as the Church of England stands. Our Church has been the Church of Ridley and Latimer and Jewel; of Hooker and Andrews and Pearson and Hammond; of Davenant and Hall and Usher and Reynolds; of Stillingfleet and Patrick and Waterland and Bull; of Robert Nelson and George Herbert; of Romaine and Toplady and Newton and Scott and Cecil and Simeon; of Bishops Ryder and Blomfield, and Jenne, and Thirlwall; of Archbishops Sumner, and Longley, and Whately; of the martyred Bishop Patteson and the late Canon Mozley. What reading man does not know that these divines differed widely about many subjects; about the Church, the ministry, and the sacraments; about the meaning of some words and phrases in the Prayer-book; about the relative place and proportion they assigned to some doctrines and verities of the faith? But they all agreed in loving the Church of England, in thanking God for her Reformation, in maintaining her protest against the Church of Rome, in using her forms of worship, and in labouring for her prosperity. They could pray and praise together. In days of darkness and persecution they drew together, like Hooper and Ridley in Queen Mary’s time, and found common ground. We may all have our own special favourites in this list of names. We may greatly prefer some of these men to others. We may think some of them were in error, and did not ‘declare all the counsel of God.’ But, after all, is there one of them whom we should like to have turned out of our communion? I reply, Not one! With all their shades of opinion, they were ‘honest Churchmen,’ and there was room in our pale for all. This is what I call the practical comprehensiveness of the National Church, and, as a Bishop, I do not want to see it altered and narrowed.

But while I say all this, I hold that there must be limits to the comprehensiveness of the Church of England. There must be certain boundaries and landmarks, for order is heaven’s first law. There was order in Eden before the fall. There will be perfect order on earth at the restitution of all things. A Christian Church utterly destitute of order does not deserve to be called a Church at all. A Church, like every other corporation on earth, must have definite terms of membership. It must have a creed, and certain fixed principles of doctrine and worship. Its members have a right to know what its ministers are set to teach.

The member of the National Church of England has a just right to expect one general type of teaching and worship, whether he goes into a parish church in Truro or Lincoln, in Canterbury or Carlisle. Different shades of statement in the pulpit he may find himself obliged to tolerate. But he may justly complain if the doctrine and ceremonial of one diocese is as utterly unlike that of another as light and darkness, black and white, acids and alkalis, oil and water. ‘Liberty of prophesying’ and free thought, in the abstract, are excellent things. But they must have some limits. Just as in States the extreme of liberty becomes licentiousness and tyranny, so in Churches it becomes disorder and confusion. The Church which regards Deism, Socinianism, Romanism, and Protestantism with equal favour or equal indifference, is a mere Babel, a ‘city of confusion,’ and not the city of God.

Now I contend that the National Church of England has set up wisely-devised limits to its comprehensiveness. These limits, I believe, are to be found in the Articles, the Creeds, and the Book of Common Prayer. If, therefore, a minister of the National Church maintains and teaches those distinctive doctrines of the Church of Rome which are plainly named, defined, and repudiated in the Thirty-nine Articles, and ignoring the public declaration which he made on taking a living, deliberately teaches transubstantiation, the sacrifice of the Mass, purgatory, the necessity of auricular confession, and the invocation of saints; or if he administers the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper with such usages and ceremonies that few persons can distinguish it from the Romish Mass; then, and in that case, I contend that he is transgressing the liberty allowed by the Church of England. He may be zealous, sincere, earnest and devout, but he is in the wrong place in a Protestant communion. He has stepped over the just limits of the Church’s comprehensiveness, and is occupying an untenable and unwarrantable position. By those limits I mean to abide, and my clergy must not expect me to sanction any transgression of them. I commend these points to the calm consideration of those clergy who may not quite agree with all I have been saying, and may think more liberty should be allowed within our pale.

I commend them especially to those zealous young men who think that the true remedy for ‘the present distress’ is freedom from State control, and disestablishment. I warn such young men to take care what they are about, and to do nothing rashly. There are times when it is better to ‘bear the ills we have, than fly to others that we know not of.’[11] A disestablished Church would undoubtedly lay down for its members certain well-defined terms of communion, and require them to be strictly observed, just as our own Established Church does now. In short, disestablishment would give clergymen no more real liberty than they possess now, and in all probability would soon be followed by disruption, and ultimately by the destruction of the Church of England.

And now let me conclude all with a request which I cannot doubt you will all approve. Let us all resolve to pray more and more for unity. It was a solemn and humbling remark which fell from Lord Macaulay’s lips, when he returned from India, and found the strife which began with the Tracts for the Times . He said, ‘I find Christians wrangling about ceremonies and forms, while millions of heathen in India are bowing down to sacred monkeys and crocodiles and cows.’ Let us never cease to plead with Him who can make men be of one mind in a house, and let us use more frequently the well-known prayer for unity, which stands in the service for the l0th of June:

‘O God the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, our only Saviour, the Prince of Peace; give us grace seriously to lay to heart the great dangers we are in by our unhappy divisions. Take away all hatred and prejudice, and whatsoever else may hinder us from godly union and concord; that, as there is but one Body, and one Spirit, and one Hope of our Calling, one Lord, one Faith, one Baptism, one God and Father of us all, so we may henceforth be all of one heart, and of one soul, united in one holy bond of Truth and Peace, of Faith and Charity, and may with one mind and one mouth glorify Thee; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.’

FOOTNOTES

1 Delivered at his primary visitation, in the Pro-Cathedral of St. Peter, Liverpool, where, with the exception of the following charge delivered in Wigan, each of the visitation charges was given.

2 Ryle had previously served in parishes in the Norwich Diocese.

3 The Secretary of the ‘Diocesan Finance Association’ informs me that at present there are only 300 lay subscribers to our Diocesan Institutions for Church Building, Church Aid, Education, etc. It appears, moreover, that in this list of 300

1 layman’s name appears 7 times.

1 layman’s name appears 6 times.

17 laymen’s names appear 5 times.

15 laymen’s names appear 4 times.

23 laymen’s names appear 3 times.

67 laymen’s names appear twice.

176 laymen’s names appear once.

4 Board Schools were set up after the passing of the Forster Education Act of 1870 during Gladstone’s first ministry.

6 Bishop of St. David’s, 1840-75.

7. ‘The composition of a purely ecclesiastical tribunal to be substituted for the present “Court of Appeal” in cases of heresy, is a problem beset with such complicated difficulties, as to render it almost hopeless that any scheme will ever be derived for its solution, which would give general satisfaction; even if there were not so many who would reject it for the very reason that it appears to recognize a principal, the mystical prerogative of the Clergy, which they reject as groundless and mischievous.’ Bishop Thirlwall’s Remains , ii. p. 135.

‘That the members of the judicial committee would ever consent, or be permitted, to renounce their supreme jurisdiction, and exchange their judicial functions in this behalf, for a purely ministerial agency by which they will have passively to accept, and simply to carry into effect, the decision of a clerical council, this is something which I believe is no longer imagined to be possible, even by the most ardent and sanguine advocate of what he calls the inalienable rights of the Clergy, so long as the Church remains in union with the State on the present terms of the alliance. But if they do not take up this subordinate position, the principle of the ecclesiastical prerogative in matter of doctrine, which to those who maintain it is probably more precious than any particular application of it, is abandoned and lost. The Church will, in their language, continue to groan in galling fetters, and an ignominious bondage.’ Bishop Thirlwall’s Remains , ii. p. 137.

8. The following evidence was deliberately given by that well-known Clergyman, the Rev. W. J. E. Bennett, Vicar of Frome, before the Royal Commission, on Ritual:

‘2606. “Is any doctrine involved in your using the chasuble?” “I think there is.”

‘2607. “What is that doctrine?” “The doctrine of the sacrifice.”

‘2608. “Do you consider yourself a sacrificing priest?” “Distinctly so.”

‘2611. “Then you think you offer a propitiatory sacrifice?” “Yes, I think I do offer a propitiatory sacrifice.”’

9. ‘We cannot but respect the courage and openness with which the leaders of the Ritualist movement avow their designs, and disclose their plan of operation. They inform us that their party is engaged in a “crusade against Protestantism,” and aims at nothing less than “re-Catholicizing the Church of England, and that, with a view to this ultimate object, they are agitating for disestablishment.” After this, it must be our own fault if we are not on our guard. But when the same persons put in a plea for toleration, I do not know how to illustrate the character of such a proposal more aptly than by the image suggested by one of themselves, of “two great camps.” It is as if one of these camps should send to the other some such message as this: “We are on our march to take possession of your camp, and to make you our prisoners; but all we desire is, that you should let us alone, and should not attempt to put any hindrance in our way” ‘Bishop Thirlwall’s Remains , ii. p. 307.

10 ‘Let the truth be upheld, though the heavens fall’. As usually quoted, ‘justitia’ takes the place of ‘veritas’.

11 Quoted from Shakespeare’s Hamlet 3. 1.