Thomas Cranmer

From a painting by Gerlach Flicke, 1546AD.

English Protestant Reformer, martyred in 1556AD.

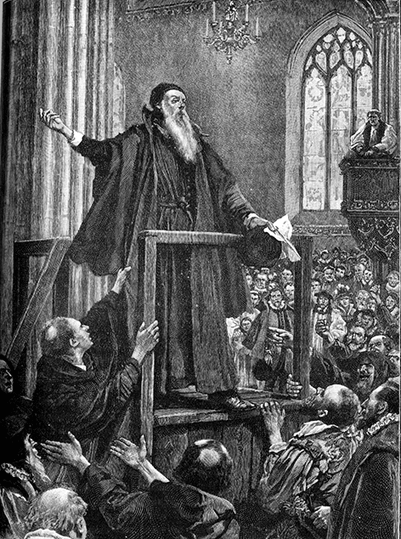

Cranmer's last testimony to the truth at St. Mary's, Oxford, 1556AD.

The dignitaries in the church waited on Cranmer’s full public recantation in conformity to his written recantations. A wooden platform had been especially made for him. After a few preliminary remarks, Thomas Cranmer said the following, as reported by separate witnesses at the church.

“And now I come,” said he, “to the great thing, that so much troubleth my conscience, more than anything I ever I did or sayde in my whole life: and this is the setting abroad of a writing contrary to the trueth, which now here I renounce and refuse as things written with my hand contrary to the trueth which I thought in my hart, written for feare of deathe and to save my life if it might bee; and that is, all such billes and papers which I have written or signed with my hand since my degradation, wherein I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand offended, writing contrary to my hart, my hand shall be first punished therefore, for may I come to the fire it shall be first burned. . . . And as for the Pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemie and anti-Christ, with all his false doctrine. . . . And as for the Sacrament, I beleeve as I have taught in my book against the bishop of Winchester, the which my book teacheth so true a doctrine of the Sacrament, that it shall stand at the last day before the judgement of God, when the papisticall doctrine contrarie thereto shall be ashamed to shew her face.”

There was now great turmoil in the church. Lord Williams of Thame, who superintended the day’s proceedings, raising his voice, addressed the archbishop, asking him whether he was in his right mind, and bidding him not dissemble.

To whom Cranmer replied, “Alas! my lord, I have been ever a man that hated falsehood, and against the truth never did I dissemble until now. I am grieved for my fault. I must now say that I believe concerning the sacrament what I taught in my book against the bishop of Winchester.”

The cries in the church now grew more menacing, and Dr. Cole from the pulpit ordered the bystanders to stop the heretic’s mouth and to take him away, which they did with some violence.

[Extract taken from the "History of the Church of England" by Rev. H. D. M. Spence, Dean of Gloucester, 1898AD.]

The burning of Thomas Cranmer, thrusting out his hand to be burnt first, as an act of repentance for having signed recantations.

WHY WERE OUR REFORMERS BURNED? (171k) pdf (119k) docx (50k) by J. C. Ryle.

Thomas CRANMER, the first protestant archbishop of Canterbury, was descended of an ancient and respectable family, and was born July 2, 1489, at Aslacton in Nottinghamshire. In 1503 he was sent to Jesus college, Cambridge, where he was elected to a fellowship in 1510, and applied himself with great industry to the acquisition of Greek, Hebrew, and theology. Before he had reached his twenty-third year he married, and having, in consequence, forfeited his fellowship, he was employed as a lecturer in Buckingham (now Magdalen) college. His wife, however, died in about a year after his marriage, and he was immediately restored to the fellowship which he had vacated.

He took his degree of D.D. in 1523, and was appointed lecturer on theology by Jesus college. In 1528, while the sweating sickness was raging in Cambridge, Cranmer retired to Waltham Abbey, where he was occupied with the instruction of two pupils, the sons of a gentleman named Cressy. This was the turning-point of his fortunes. Henry VIII., who was then earnestly pressing his divorce from Queen Catherine, had at this time made an excursion to the neighbourhood of Waltham, and Gardiner and Fox, afterwards bishops of Winchester and Hereford, were in attendance upon the king, and accidentally meeting Cranmer at Mr. Cressy’s table, began to discuss with him the absorbing question of the divorce. Cranmer suggested the propriety of “trying the question out of the word of God,” a course which clearly implied that it should be decided without the authority of the pope. Fox, who was then the royal almoner, mentioned this recommendation to the king, and Henry, eagerly catching at the hint, “swore by the Mother of God, that man hath the right sow by the ear.” Cranmer’s attendance was immediately required at the palace, and he was commanded to reduce his opinion to writing, and to devote his whole attention to the furtherance of this important matter. He was shortly after appointed archdeacon of Taunton, and one of the royal chaplains.

Henry was not yet prepared to hazard an open rupture with the pope, and sent Cranmer, along with several others, on an embassy to Rome about the close of 1529. The mission was unsuccessful, however, and shortly after his return, Cranmer was sent in 1531 as ambassador to the emperor on the same business. During his residence in Germany he married, about the beginning of 1532, Anne, niece of Osiander, the pastor of Nuremburg. Shortly after, Archbishop Warham died, and Cranmer was recalled to fill the vacant see. He was consecrated March 30, 1533. A few weeks later, 23rd May, 1533, Cranmer declared Henry’s marriage with Catherine null and void; and on the 28th he publicly married the king to Anne Boleyn, whom Henry had privately espoused in the month of January. In 1536, in virtue of his office as primate, Cranmer declared the marriage of Henry to this unhappy princess void; and again, in 1540, he presided at the convocation which pronounced the unjustifiable sentence of the invalidity of the union between the king and Anne of Cleves. In these transactions, it must be admitted, that Cranmer appears to little advantage. Meanwhile the archbishop took a conspicuous part in promoting the progress of the Reformation. He assisted in passing several statutes which materially diminished the power of the pope in England. He set on foot a translation of the Bible, assisted in the correction of a second edition of the “King’s Primer,” and urged the king to take steps for the suppression of the monasteries, and the application of their revenues to the advancement of religion and learning.

When Henry lavished these funds upon unworthy favourites, Cranmer had the boldness to remonstrate against this misappropriation of the national property. In 1538 he strenuously resisted in the house of lords, at the risk of the king’s displeasure, the enactment of the obnoxious “ Six Articles” proposed by the duke of Norfolk. The Reformation continued to gain ground, and Cranmer exerted himself, in the face of great opposition, to extend its benefits throughout the kingdom. Books of religious instruction were circulated among the people, and mainly through his influence every man was allowed to enjoy the inestimable boon of reading the Bible in his mother tongue. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that Cranmer had deeply imbibed the persecuting spirit of the old religion, and the share which he took in the condemnation of John Frith, Andrew Hewat, Joan of Kent, and others who suffered for their religious belief, has left a deep stain upon the primate’s character. On the death of Henry in 1547, Cranmer was appointed by his will one of the regents of the kingdom; and by his talents, learning, and high station, contributed largely to the advancement of the protestant cause. He was the author of four of the Homilies, and one of the compilers of the Service Book, and the Articles of Religion, originally forty-two in number, were mainly, if not exclusively, drawn up by him.

Edward VI. died in 1553, and the reluctant accession of the archbishop to the injudicious scheme of elevating Lady Jane Grey to the throne, combined with his religious opinions, rendered him peculiarly obnoxious to the bigoted Queen Mary. In September, 1553, he was committed to the Tower along with Latimer and Ridley; and in March, 1554, he and his fellow-prisoners were removed to Oxford, and confined in the common prison called the Bocardo. They were ultimately condemned as obstinate heretics. Ridley and brave old Latimer underwent their cruel sentence with indomitable resolution; but the fortitude of Cranmer gave way under the pressure of misery, and the prospect of tortures and death, and he was induced by the hope of saving his life to sign no fewer than six recantations. His enemies, however, had determined that his abjuration of the protestant faith should avail him nothing, and this venerable and learned prelate was, accordingly, condemned to the flames. When brought out to execution, 21st March, 1556, he was exhorted to repeat his recantation; but, to the surprise and dismay of his adversaries, he openly declared his adherence to the reformed religion, and expressed his deep penitence for his unworthy denial of the faith. He was fastened to the stake opposite Baliol college, and suffered the cruel torture of the flames with a heroic fortitude, which his timidity and recent wavering conduct had not led his friends to expect.—Rev. James Taylor, D.D. [Imperial Dictionary of Universal Biography, 1878AD.]

Reign of King Henry VIII. (215k) by Daniel Neal, from his History of the Puritans (1855AD edition) pdf (140) zip (46k)

Reign of King Edward VI. (226k) by Daniel Neal, from his History of the Puritans (1855AD edition) pdf (137k) zip (46k)

39 Articles of Religion (102k) Church of England (1571AD edition) pdf (50k) zip (13k)

A Fruitful Exhortation. (90k) A Homily on the "Reading and Knowledge of Holy Scripture." As first published in 1562AD. (1800AD edition.) pdf (32k) docx (26k) zip (21k)

Misery of Mankind . . . by his own Sin. (107k) A Homily on Mankind's sinfulness. As first published in 1562AD. (1800AD edition.) pdf (33k) docx (26k) zip (22k)